I’m tackling a big question with this article. But it’s a question that demands an answer. Is dividend investing evidence-based?

Evidence-based investing is the process of making decisions based on academic research and long-term historical data rather than short-term trends and human judgement. I am all about evidence-based investing. It’s not sexy or exciting, but that’s science.

One clear conclusion is that a simple, low-cost, broad-based index fund is a great approach to investing. The SPIVA reports prove year in and year out that passively investing in an index ETF will outperform the vast majority of active investors, especially when fees are taken into consideration.

I read A LOT of content created by index investors because they tend to be very evidence-based, promoting financial concepts that I support 100%: don’t try to pick hot stocks, don’t try to time the market, keep costs low, invest for the long-term, etc. But some of these people have come to a conclusion that I can’t get behind: that indexing is the ONLY evidence-based way to invest.

This is simply not true. Dividend investing is evidence-based too, it’s just not as easy to understand as indexing. If you ever find yourself in a debate with a die-hard index investor, this post will give you what you need so that you both understand why dividend investing is evidence-based.

Why are some evidence-based index investors suspicious of dividend investing?

Over the years, I’ve come up against some tough arguments:

- If professional fund managers can’t beat the market, how can dividend investors?

- If it really worked, why isn’t everyone doing it?

- Ignoring non-dividend payers results in a less diversified portfolio, which is, therefore, riskier than a more broadly diversified portfolio

- Holding less than 30 (or so) stocks increases volatility

To summarize the bottom line for dividend investing skeptics it boils down to this: No one can reliably beat the market over the long term by buying individual stocks because the market is efficient.

If the market is efficient, how can dividend stocks outperform?

At this point, if you’re expecting me to refute the efficient market hypothesis, well, that’s not going to happen. I agree with the skeptics – the market is efficient – at least sufficiently efficient that there’s no point nor evidence to support a strategy that involves picking hot stocks or timing the market (BTW, here’s a great book on the subject).

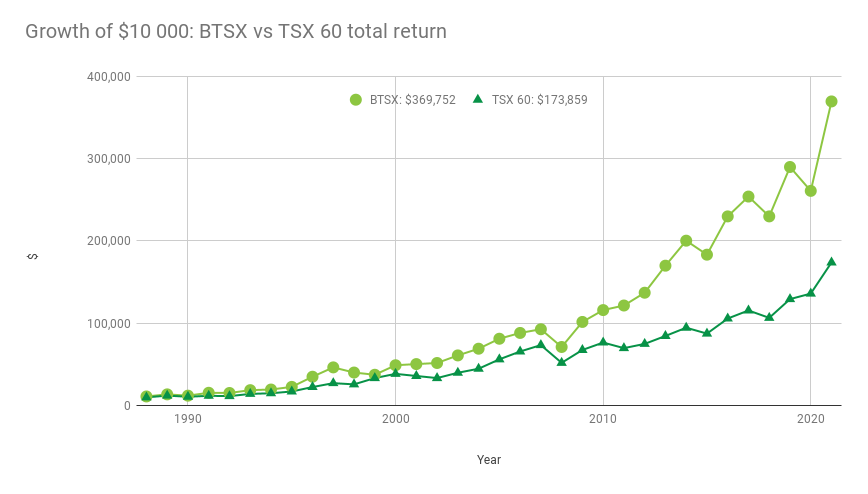

And yet, we have a 30+ year track record of Beating the TSX, a dividend-based strategy, well, beating the TSX. And not just by a little bit. Over the last 30 years, BTSX portfolios have outperformed the TSX60 by almost 3% per year. That means that, by the end of 2021, $10 000 invested using the BTSX strategy would be worth $369,752. That same $10 000 invested in the benchmark index would be worth only $173,859 – a 113% difference.

Could this be a fluke? Frankly, I’d be nervous if BTSX’s performance was out of line with dividend investing in general. But, according to independent research by RBC Global Asset Management, a dividend investing strategy is no roll-of-the-dice. There is something about Canadian dividend-paying stocks that has resulted in long term outperformance over non-dividend payers. Their report shows that, since 1986, Canadian dividend-paying stocks have averaged 9.1% per year vs only 1.2% for non-dividend-payers. On top of that, dividend-payers displayed far lower annualized volatility than non-payers (14% vs 24%).

This is 35 years of Canadian data and it’s pretty compelling, but is there a better source of empirical data? You bet.

More evidence that dividend investing works

This 2019 study by the editor of Financial Analysts Journal, showed that from 1802 to 2002, dividends and dividend growth accounted for 73% of the total annualized return in U.S. stocks.

What about the rest of the world? This study showed that from 1900 to 2005, the total real return of stocks across 17 developed countries (including Canada, the U.S., and what are now EU countries) averaged about 5%. The average dividend yield made up 90% of that return at 4.5%.

The best evidence for dividend investing

Perhaps the most comprehensive and relevant data regarding the long term performance of dividend-paying stocks comes from one of the godfathers of multi-factor asset pricing models himself, Kenneth French. If you’ve heard of the “Fama and French 5-Factor Model”, you’ve heard of him. He’s kind of a big deal.

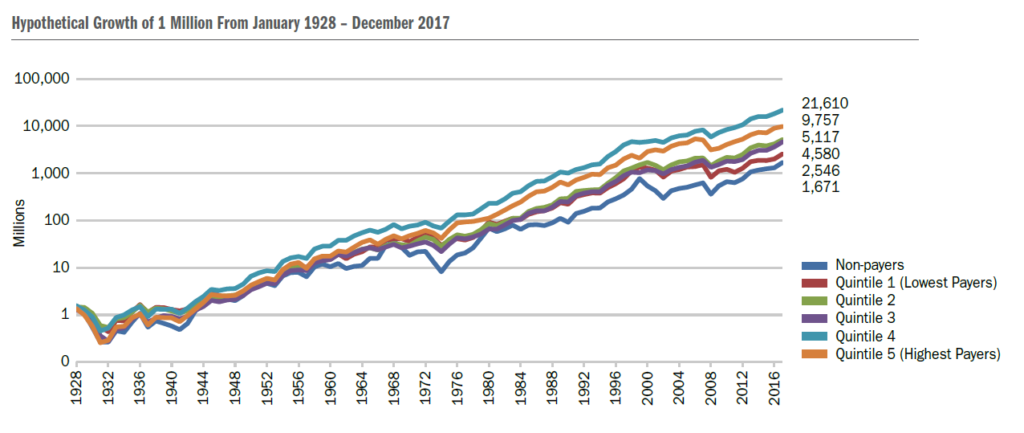

You can access Kenneth French’s Data Library HERE. Not needing to reinvent the wheel for this post, I borrowed heavily from this white paper by Heartland Advisors which crunched original stock data from the US Stock Database ©2018 Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) and the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. By comparing non-dividend-paying stocks and five portfolios of dividend-payers (grouped by dividend yield quartile) from 1928 to 2017, some incredibly clear and powerful findings emerge.

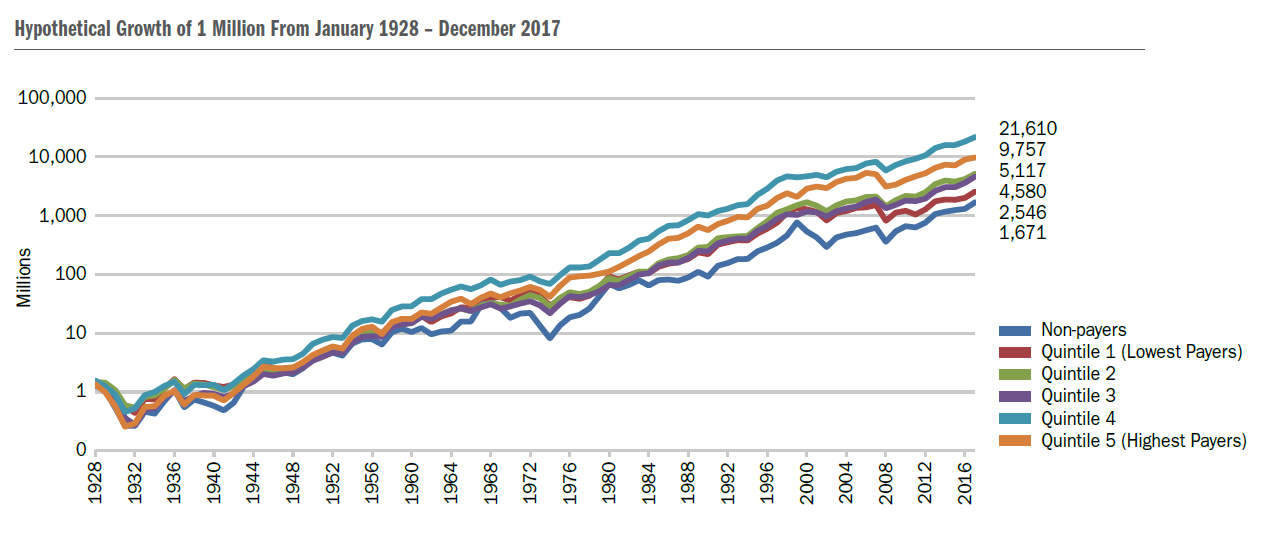

The most important chart from this paper is this one. From it, we can draw several findings.

Finding #1: Dividend payers outperformed non-dividend-payers

Notice this chart is logarithmic, not linear. Thus the long-term performance difference between dividend-payers and non-payers is even more pronounced than it might first appear. Have a look at the final numbers on the right: The average dividend payer returned three times as much as the average non-payer.

Finding #2: The highest-yielding stocks did not perform as well as the second-highest yielding stocks (by quintile)

This is an important point. Don’t chase yield. Why do the highest-yielding stocks underperform? Likely because the high yield reflects a depressed stock price. For big, fundamentally stable and profitable businesses, this can be a great opportunity. But there are very few companies that can sustain a 7%+ dividend yield. Remember, dividend cutters underperform even non-payers, so caution is warranted. In my opinion, this is why dividend-payers in quintile 4 are the best performers.

Note: Beating the TSX selects the highest yielding stocks from the TSX 60, but these are generally not the highest yielding stocks overall because the TSX 60 pre-selects large, stable companies

Finding #3: Dividend-paying stocks reliably outperform non-payers with lower volatility

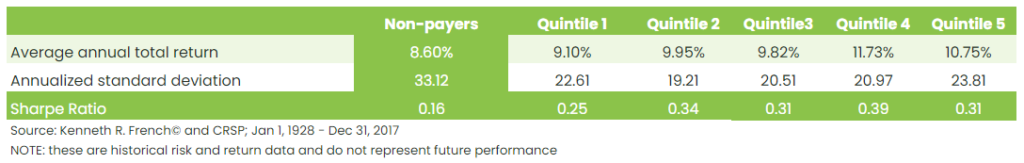

Have another look at the chart above and notice the relative smoothness of the dividend-payers vs. the bumpiness of the non-payers. This reveals the fact that the average dividend-payer is far less volatile than the average non-payer. Here are the numbers by quartile:

Understanding risk-adjusted returns is critical as an investor. The Sharpe Ratio is one measure and clearly shows that the risk-adjusted returns of dividend-paying stocks are far superior to non-payers.

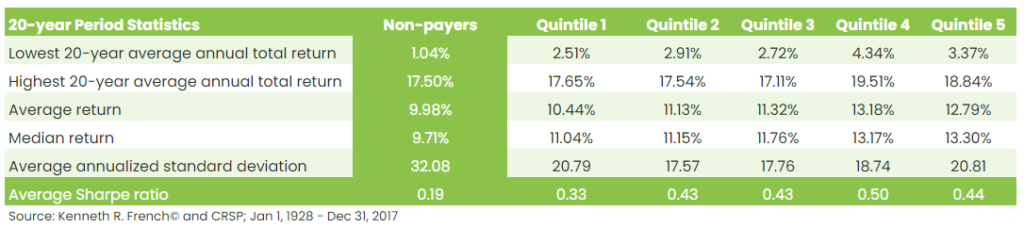

Finding #4: Dividend-payers have provided higher returns and lower risk over 20-year holding periods

Only looking at very long-term data, 90 years in this case, can give the impression that investing in stocks is a consistently profitable endeavor. But the performance of stocks is a roller-coaster, not an escalator. What happens when the data is analyzed in more realistic 20-year chunks? In this way we can get a feeling for how dividend-payers vs non-payers perform in different kinds of markets.

The following table shows that, in general, dividend-paying stocks outperformed non-payers in the vast majority of 20-year periods between 1928 and 2017.

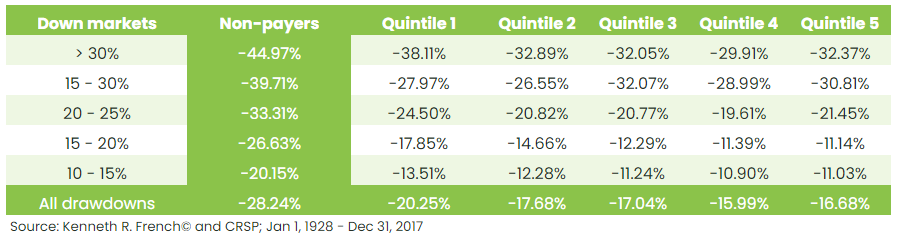

Finding #5: Dividend-payers outperform non-payers in down markets of all magnitudes

Warren Buffet is famous for saying “The first rule of investing is don’t lose money. The second rule is never to forget rule number one.” So, how have dividend-paying stocks performed in down markets compared to non-payers? Quite well. During the average drawdown, dividend-payers in Quintile 4 decreased only about half as much as non-payers.

When there’s “blood in the streets”, investors seek safety and dividend-paying stocks offer such refuge, especially when interest rates are so low. Furthermore, as the stock price of dividend-payers goes down, the dividend yield goes up, so the worse things get, the better dividend stocks look.

Understanding the skeptics

Interestingly, academically-minded dividend skeptics often draw on the Fama and French 5-factor model as support for their position. Given the data above, this confused me for a long time. What I now understand is that Fama and French chose not to include dividends as a factor in their asset pricing model for good reasons. Other, more fundamental factors, like value, profitabilty, and company investment policy were more useful in creating their tool. Here’s the key: those factors tend to lead to outperformance and dividend-payers tend to have these factors.

One of my go-to sources of excellent financial commentary, Benjamin Felix, is also a die-hard index investor. Even though he seems to have a blind spot for dividend investing, I highly recommend the content he creates because it is very thorough and useful. But, even Ben, in the middle of an article attacking dividend investing (I encourage you to read it to get the other side of this debate), states:

“Dividend stocks, particularly dividend growth stocks, have excess exposure to the value, profitability, and investment factors. That is what explains performance differences . . .”

Far from being a reason to avoid dividend stocks, it seems to me that the data points to dividends as being an effective identifier of those very factors that lead to outperformance. In other words, a simple, easy-to- use dividend strategy gives DIY investors access to factors that have been proven to generate higher returns with lower risk.

Caveat emptor

That’s not to say you can’t go wrong with dividend investing – you certainly can. Aside from chasing yield, here are a few challenges that dividend investors face that index investors don’t need to worry about:

- Under-diversification: it can be challenging to build a portfolio that is diversified across sectors using dividend stocks, especially in Canada. In general, holding a smaller number of stocks can lead to a higher dispersion of returns. On the other hand, this is at least partially offset by the lower volatility of dividend-payers. Personally, I think it is important to diversify internationally and I do this using index funds that exclude Canada.

- Dividend cuts: Companies that cut their dividends tend to underperform. It is important to realize that in the analysis above if a company cut its dividend, it would switch groups. Thus, the subsequent underperformance would not be fully captured in the original category. Unpredictable dividend cuts will happen, and caution is certainly warranted. The easiest way to manage this risk is to avoid very high-yielding stocks, especially when the earnings and cash flow of the company make sustaining the dividend unlikely. Index investors don’t have to concern themselves with this extra bit of work.

- Behavioural risk: There’s no doubt about it – it’s easier to be an index investor. When you’re managing a portfolio of 10+ dividend-paying stocks, there is a little more work involved, but more importantly, there is a greater risk of making errors in judgement. The temptation to time our buys and sells, or take gambles on stocks we have a “good feeling” about is real – probably more so for stock vs. index ETF investors. Buying dividend-paying stocks can also be a “gateway drug” to speculating on other equities. I say all this from experience; being a dividend investor requires a higher level of self-restraint.

Conclusions

Dividend investing is indeed evidence-based, but it’s slightly more complicated than index investing with a few important trade-offs to be aware of. For those who want to keep things simple and avoid the extra work and complexity that goes along with purchasing individual stocks, a low-fee index-ETF approach is a great way to invest. I recommend it all the time, especially for people without large amounts of money to invest or significant comfort and experience with investing.

But the data is clear: dividend-paying stocks have offered higher returns and lower volatility than non-payers in many different market conditions. For Canadian investors, Beating the TSX has proven to be a simple and effective tool for building a portfolio of dividend-paying stocks that has performed exceptionally well.

A lot of work went into this article. If you found it informative and/or helpful, please consider donating to help with the cost of running this blog – I’d really appreciate it! Half of all donations are given to Doctors Without Borders.

You have written 2 excellent articles on this subject with great evidence. What is never discussed in articles in the general literature is AFTER TAX RETURNS. This would reduce the gap in performance between dividend investing and the indexers. Many academic articles are geared to an audience that manages non-taxable pension assets.

I believe the dividend growth strategy is an excellent option for

1. Someone who can utilize the DTC and can generate income at a zero or very low tax bracket.

2. An RRSP/TFSA which is not taxable

I am not sure about this but I believe in the US market in the GFC of 2008/2009 even the widows and orphans stocks took it on the chin ( eg Citibank ) ,so this this strategy has held up well in the Canadian Market. I think a US investor would have to be very disciplined to stay the course in that calamity -you have already alluded to the behavioral risk, I supposed that’s true of index investing also.

Keep up the great posts.

Great comments, Lyndon. The tax situation gets even more complicated, of course, because different investors will have different incomes, from different baskets, etc. So, it becomes very complicated very quickly. I suspect that the tax implications would be less than some would think, but it’s still a good point you raise. Perhaps I could run a few scenarios and create a post.

Matt – as usual – I like your well researched articles.

Since Lyndon raised the tax issue, let me add another tweak to that.

I am a Canadian TAX resident, with RRIF and TFSA accounts, as well as non registered investment accounts. The Canadian DTC has for the last 20 years or so caused me to ( be confused?) allocate my dividend generating ( both US and CAD ) investments away from the tax deferred RR accounts accounts. With hindsight, I could have followed a dividend strategy inside the RR accounts, not the TFSA for US equities.

However the superior return for Canadian dividend investments is in part related to the DTC and hence not available/ applicable if investing inside the RR accounts.

In addition, I have been torn as to where to invest for capital gains, since doing so inside a tax deferred RRSP or RRIF account effectively THE WAY I UNDERSTAND the Canadian tax regulations, will generate (lower taxed capital gains into eventually higher income taxed RRIF withdrawals. That does not appeal to me.

My choice with hindsight has been poor, as I have l et the tax considerations steer me into an unfortunate asset mix with too much interest income inside the RR accounts. MY MISTAKE!

I think I have a (complicated) way of investing with any possible losses allocated to the RR accounts and the lower taxed (capital) gains arising in non registered margin accounts. BUT that is a complicated structure ( not capital efficient) and I have so far shied away from it for that reason.

I look forward to your views on investing taking the specific Canadian tax implications into account

As a general rule, I am in the camp of “Don’t let the tax tail wag the investment dog” – i.e. Don’t let tax implications direct investment decisions. I’ve read numerous analyses over the years and the consensus always seems to be that the financial impact of various tax minimization strategies is small to nil, while causing other issues.

Ben Felix, who I mention in this post, did a great podcast on this a while back that is worth a listen (or read the show notes): https://rationalreminder.ca/podcast/158

Thanks for sharing your experience, BEK. To clarify one point from your third paragraph, however, the outperformance of dividend-payers vs non-payers is independent of taxation and is, therefore, absolutely applicable when investing in registered accounts.

What a great article. You do your research. And I now always point people to your website when trying to explain dividend investing. The BTSX is for the Canadian investor, and should not be compared to US dividend investing. Their regulations are different. But for any DIY investor I think this is the easiest strategy to follow and doesn’t take much time. No need to use ETF’s where you get them all, good, bad, and mediocre.

Matt, that “something” that has resulted in in the outperformance of Canadian dividend stocks is the value premium. But dividend stocks give you only weak exposure to the value premium. So if you want exposure to these premiums, you are better off investing in value index funds that will give you a greater exposure to the value premium as they include non divided payers that also are value stocks. By only investing in dividend payers, you are restricting your universe of stocks to invest in, so end up with a less diversified (and therefore riskier) portfolio, and one that has less exposure to the value premium – one of the drivers of return in the market.

As Ben Felix points points out, dividend stocks give you exposure to the value premium (and other premiums), but it is a weak exposure compared to what you can get by buying index funds that seek exposure of these premiums from all stocks, not just dividend payers.

I do concede that in Canada there are not yet well constructed ETFs that give you good exposure to these premiums and a low cost (unlike in the US market, AVUV and in the developed foreign markets, AVDV), but I am sure that will change with time. But I’m not sure that following a stock picking strategy is the answer to that problem. I prefer to stick with total market index funds in the Canadian market and have a small cap value tilt the US and international markets. If good quality small cap value funds become available for the Canadian market, I’ll go with them.

I’m the first to admit that behaviour is the most important part of investing, so you must be comfortable with whatever strategy you prefer. A suboptimal portfolio you can stick with is better than an optimal portfolio you can’t stick with. But it’s helpful to understand the science of investing to help make the strategy decision.

https://www.etf.com/sections/index-investor-corner/swedroe-irrelevance-dividends?nopaging=1

Pingback: Expensive Self-Talk For Investors — Physician Finance Canada