John is proud of his son Chad. Last year he landed his first full time job and every month he saves money and invests it. One day they are talking on the phone and Chad says, “Dad, I know you like your dividend stocks, but index investing is really the way to go.”

John replies, “Index investing is great, Chad – as you know I use index ETFs to get exposure to international markets. But for my Canadian equities, my dividend stocks have always treated me very well.”

“Yeah, I know they’ve done well, but an index fund is safer because you own all the companies in the index, not just a handful. By owning fewer stocks you’re taking on more risk.”

“That’s why I stick to blue-chip dividend-payers . . . but I see what you mean. Sometimes my portfolio behaves very differently than the benchmark index. Often that’s positive, but sometimes it under-performs. Overall, I don’t think my dividend stocks are more risky than an index fund, but I have to admit, I’ve never confirmed that.”

You’re probably reading this because you’re interested in growing your wealth. Perhaps you’re familiar with the fact dividend-paying stocks have historically outperformed non-dividend-paying stocks and you’re looking to optimize your own returns. Higher returns = better investments, right?

Well . . . maybe. Those who prefer index investing might point out that by eschewing the broad diversification of index ETFs and purchasing a smaller number of individual stocks, dividend investors are, by definition, taking on more idiosyncratic risk. The reasoning is that higher risk leads to a higher dispersion of returns – i.e. more portfolio volatility.

This is a valid concern – just think about stocks vs. bonds. Stocks are more volatile than bonds so investors demand higher returns to compensate for higher risk. If the risk is not compensated appropriately, the bonds might be better investments.

And so, even if dividend-paying stocks have outperformed their benchmarks, that doesn’t necessarily mean that investors have been adequately compensated. Thus, we need a way to understand investments that incorporates both risk and return. We call this “risk-adjusted returns”, and it’s probably simpler than you think.

What are risk-adjusted returns?

A risk-adjusted return is a calculation of the profit or potential profit from an investment that takes into account the degree of risk that must be accepted in order to achieve it (Investopedia).

Usually the risk of an investment is measured against that of a virtually risk-free investment. We will be using Canada Savings Bonds in our calculations.

How is risk measured?

There are two common ways to measure the risk of an investment: beta and standard deviation.

Beta

Beta is a measure of volatility compared to the market as a whole. The term “beta” is often used interchangeably with risk or volatility, but this is misleading. Beta is not a pure measure of risk or volatility, but rather a measure of how a stock’s performance differs from that of the underlying index.

Here is a great post that will help you understand alpha and beta.

Beta is generally calculated using five-year data. A beta of 1.0 means the value of a stock (or portfolio), on average over the last five years, has moved in lock-step with the underlying index. If the index went up 10%, the stock did too. A higher beta of, say, 2.0 would mean that a stock has, on average, moved twice as much as the underlying index; a 10% rise or fall in the index would be accompanied by a 20% rise or fall in the stock, respectively. Whereas a beta between 0 and 1 indicates returns that are correlated but have lower volatility than the index.

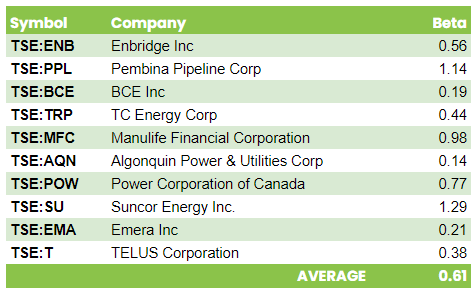

Enbridge (ENB), our highest-yielding BTSX stock, for example, has a 5-year beta of 0.56. Thus it tends to move with the market while being about half as volatile. CNQ has a 5-year beta of 1.39, indicating higher relative volatility than the index. The utilities AQN and FTS have betas barely over zero (0.14 and 0.04, respectively), indicating returns that are hardly correlated with the market at all. I think of such stocks as being almost bond-like.

The average 5-year beta of our current Beating the TSX list shown below.

There is plenty of evidence to show that dividend-paying stocks as a whole have lower beta than non-dividend-paying stocks. This is one of the only “free lunches” to be found in investing: lower volatility and higher historical returns. So far, so good, but we need to dive deeper.

Standard deviation

Standard deviation is a statistic that reflects how variable the results within a dataset are relative to the mean of that same dataset. Bitcoin has a huge standard deviation. Fortis (FTS) has a small one. Standard deviations are not compared to a benchmark, rather they are a measure of internal variability.

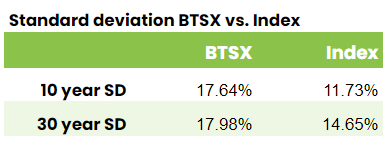

When measuring the risk-adjusted returns of Beating the TSX stocks, standard deviation is useful in a practical sense because we have access to 30 years of portfolio returns vs only five years of data for beta.

Looking back at the total returns of Beating the TSX portfolios vs the benchmark, we can see that BTSX had higher variability and thus, a higher dispersion of returns.

Interesting. Even though BTSX stocks appear to have lower beta, on average, over the last three decades, portfolio returns have actually been more volatile. BUT, there are two things we must remember that dividend critics often forget:

- Standard deviation doesn’t distinguish between variability that is higher or lower than the mean. Thus, really good years (like 2021) will increase standard deviation and be good for investors – i.e. not all volatility is bad.

- If the portfolio with higher standard deviation has also performed better overall, investors may have been compensated for that variability. This is exactly why we need to understand risk-adjusted returns.

Still with me? Great, because we’re ready for the good stuff.

The most common way to measure risk-adjusted returns

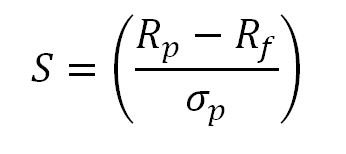

Perhaps you’ve heard of the Sharpe ratio. It measures investment returns against a risk-free rate such as those that investors might receive from treasury or Canada savings bonds. It is calculated by taking the return of the portfolio, subtracting the risk-free rate, and dividing this result by the investment’s standard deviation. The higher the Sharpe ratio, the better.

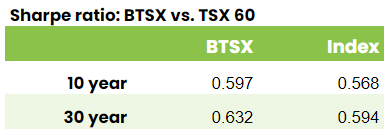

So, using the standard deviation data above and the historical BTSX performance data, we can finally compare the risk-adjusted returns of Beating the TSX vs. the TSX 60 benchmark. Let’s start with a 10-year Sharpe ratio for BTSX:

Rp = 12.29% (BTSX 10 year average total return)

Rf = 1.76% (current 10 year Canada bond rate)

σp = 17.64%

BTSX 10 year Sharpe ratio = 0.597

Now, we can do the same calculation for the index:

Rp = 8.42% (TSX 60 10 year average total return)

Rf = 1.76% (current 10 year Canada bond rate)

σp = 11.73%

Benchmark 10 year Sharpe ratio = 0.568

What we can see from these numbers is that over the last ten years, Beating the TSX investors have enjoyed not just higher returns, but higher risk-adjusted returns. Just for fun, I calculated the 30-year numbers. Here is a summary:

Using the Sharpe ratio, it would appear that Beating the TSX investors have indeed been compensated for any additional volatility they have endured over the last 30 years. But this measurement actually understates the risk-adjusted benefits of Beating the TSX.

Improving on the Sharpe ratio

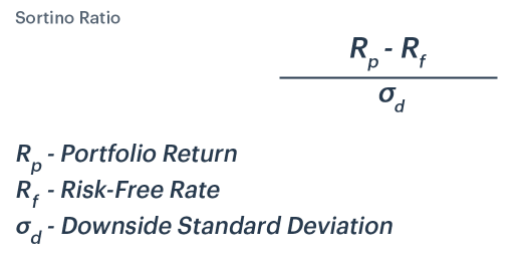

The problem with the Sharpe ratio is that it relies on standard deviation as a measure of risk and standard deviation doesn’t distinguish between variability to the upside or downside. When it comes to investing, it’s really downside volatility that is risky. Enter the Sortino ratio, which only considers downside volatility:

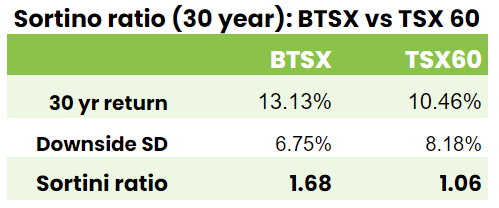

By only considering downside standard deviation, the Sortini ratio doesn’t penalize a portfolio that has displayed outsized positive variability – something all investors hope for. However, because we are only using the variability of down years, we only obtain useful results by using our 30-year data. As you can see, Beating the TSX portfolios now appear even stronger on a risk-adjusted basis:

It’s worth noting that there is a good reason for dividend-paying stocks to display lower downside volatility. As stock prices fall, yields of dividend-paying stocks go up, making them more and more attractive to investors. Thus, when markets are falling, dividend stocks tend to be more resilient than non-payers. I call this the dividend shock-absorber effect. This effect explains the lower beta of dividend-paying-stocks, while the slightly higher standard deviation can be explained by the occasional dividend-cutting “loser” and the variability of positive returns.

The bottom line

There are other ways to calculate risk-adjusted returns, but these are the most relevant for our purposes as long-term dividend investors. For me, the evidence is quite compelling: Beating the TSX investors have been more than fairly compensated for any additional risk they might have taken on by owning fewer stocks. In fact, one could easily make the argument that, in the long run, Beating the TSX has been both less risky and more profitable than index investing in Canada.

Risk-adjusted returns - a summary

- Investors must be compensated for taking more risk with higher returns

- Portfolios with different risk profiles can be compared using “risk-adjusted returns”

- There are two common measures of risk/volatility

- Beta measures the volatility of an investment relative to its benchmark

- Standard deviation measures the volatility of a portfolio relative to its average returns over time

- The Sharpe ratio weighs risk-adjusted returns by measuring investment returns against a risk-free rate, adjusting for standard deviation of returns. The major weakness of this metric is that high positive returns are deemed as “risky” as very low returns.

- The Sortino ratio seeks to improve upon the Sharpe ratio by only including downside standard deviation.

- Both the Sharpe and Sortino ratio show that Beating the TSX has outperformed the benchmark ETF on a risk-adjusted basis over the last 30 years.

If you found this post informative and/or helpful, please consider donating to help with the cost of running this blog. Don’t forget, half of all donations are given to Doctors Without Borders.

Very interesting data Matt. I tend to measure volatility using beta. It is a relative measure and shows me how volatile a stock is vs. the overall market. Time and again academic studies have shown that stocks with lower beta outperform. Why? I think the reason is that high volatility stocks (e.g., marijuana stocks, NFTs, tech stocks, small caps, etc.) tend to attract speculators not investors and these players make a living from darting in and out of the market, increasing the volatility but decreasing the overall return that we BTSX investors rely upon. Fortunately, stocks with higher dividends usually don’t play a part in speculator’s portfolios. As a general rule I suggest avoiding speculative stocks and sticking with proven investments. Not only will your returns be higher but you will sleep better also.

You are absolutely right, Dave. The fact that low beta stocks have provided better-than-average returns is one of the only “free lunches” in investing and I think your explanation is correct. Once again, even though it can be hard to resist the allure of what’s popular, when it comes to building wealth, boring is better.

Just wondering about the SORTINI Ratio? I see a lot printed about the SORTINO Ratio but not much, if anything about SORTINI. Are these the same thing or just a typo?

Thanks for the article and I agree on the value of knowing what your risk adjusted returns are.

Al

Oops – Apparently I got my vowels mixed up. You’re right – it’s “Sortino ratio”, not Sortini. I have edited the post. Thanks, Al.

Thanks, I enjoy the article. You always make me think about improvements that I can make on my investments. And I always learn something new from your writings.

I know that data for VDY (Vanguard FTSE Canadian High Dividend Yield Index ETF) is only available since 2013, but that may be a better index to compare BTSX with.

I know BTSX are beating VDY since 2013, but it just feel it would be a more apples to apples comparison.

Hi Tom, thanks for the kind words.

I can see why VDY would appear to be a “more apples to apples comparison” with BTSX – no argument there. BUT, it is an ETF, not an index. For a variety of reasons it is standard practice to measure funds and portfolios against a broad index, rather than against other funds. In the case of Beating the TSX, the whole point is to see if our simple method will beat the TSX 60. This is the comparison that we’ve been making for over 30 years. Now, that is not to say that we can’t ALSO compare BTSX to VDY. As you point out, BTSX’s returns are a little better, but there are some investors who would choose the simplicity of an ETF – no problem.

Thanks for the input, though, Tom. Perhaps other readers will weigh in. I wonder if a post comparing BTSX to various high yield funds would be of interest to readers.

Excellent write-up (as usual Matt). Blue-chip dividend growers are less speculative, less volatile. BTSX portfolio is for investors, not traders or speculators. Intuitively it makes sense that it would be less volatile and more profitable for investors.

Thanks for the comment, Sil. Given how efficient markets are, it’s hard to believe (especially for index investors) that there is a method that generates better long-term results with lower risk. Skepticism is a very appropriate reaction to such claims, so it’s important that we take a long hard look at the data. There is more to dig into and I’m looking forward to it.

Man. Thanks again Matt for a fantastic, data-driven post. I think the conclusions you have presented are quite a big deal. For me, even though I’ve always been a huge BTSX fan and it’s been the core of my portfolio for 12 years, I still have, consciously, assumed that an index strategy is “safer.” I’ve been ok with taking added perceived risk by using BTSX because I have a long time horizon and have always accepted a slightly higher risk to gain a higher reward of those beating the index results. But, now it appears those are purely that – perceived, not real – risk. Looking back, I wish I would have used BTSX in my kids’ RESP for the front end of their lives, as I always used broad Canadian and US market ETFs (XIU, XSP primarily) because I just thought they were less risky. Apparently not.

Thanks again

Thanks for the comment, Chad. I had a lot of fun researching and writing this post because I didn’t know what I was going to find. The content was a little technical, but the results are profound.

Pingback: Is dividend investing evidence-based? 5 key findings — DividendStrategy.ca