“Investing is not a game where the guy with the 160 IQ beats the guy with the 130 IQ. Once you have ordinary intelligence, what you need is the temperament to control the urges that get other people into trouble in investing.”

– Warren Buffet

If you’re a zebra grazing on the savannah, what would trigger your stress response? Perhaps you spot a lion approaching in the grass and in a moment everything changes. You snap to attention, cortisol surges, pupils dilate, your heart starts pumping, nerves and muscles prime themselves for action. At the same time, blood is shunted away from important but non-essential processes like digestion, reproductive organs, and immune function. Those things can wait. Survival can’t.

Like zebras, we are hard-wired to shift our focus from long-term to short-term when under stress.

Once the danger passes, balance is restored and all those vital long-term functions come back online. In biology, we call this homeostasis: “a self-regulating process by which an organism can maintain internal stability while adjusting to changing external conditions.”

Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers

Robert Sapolsky is a Stanford biologist who wrote a book in the 1990s called “Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers”. The central premise of the book is that stress is episodic for animals like zebras – it comes and it goes. Although they remain vigilant of danger, they spend most of their time in a healthy state of self-regulation. They don’t get ulcers.

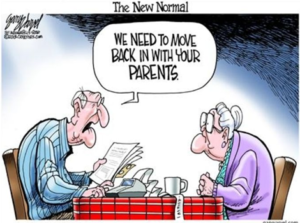

For humans, on the other hand, stress is often cognitive rather than physical and, even more importantly, it tends to be constant rather than episodic. Job stress, relationship stress, financial stress – or often a combination of all three – can be unrelenting.

A different kind of stress

Financial stress is particularly damaging. Research shows that people who are dealing with financial stress are:

- Twice as likely to report poor overall health

- Four times as likely to suffer from sleep problems, headaches and other illnesses

- More likely to experience strain in your personal relationships

- Have a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease, anxiety and depression

It’s not just a lack of money that causes financial stress. Anything that causes you to worry about your financial future can be a trigger.

More stress = worse decisions

Ironically, the more we worry about money, the worse our financial decisions tend to be. Why? Because the worry makes us short-sighted.

Recently, the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank has rattled investors around the world. It’s the threat du jour and our rational minds might know that a year from now this will be a distant memory. But here’s the thing: our biology doesn’t know the difference between a lion attack and a potential bank run.

Fear is fear. Cortisol rises, blood pressure goes up, and homeostasis is told to shut up and wait. Long-term investment plan? Screw that. We have to survive NOW.

The more intense our stress response, the more hyper-focused we become on simply surviving. Stress is correlated with bad decision-making. Numerous studies back this up: When we feel threatened, we have a bias toward short-term thinking and tend to make decisions that are not good for us in the long term.

Stress seduction

If you watch the financial news, you will be barraged with reasons to be afraid. Fear sells – we’re seduced by it – because, like the zebras, we are hard-wired to be on the lookout for danger. The difference is that no one benefits from scaring the sh*t out of zebras with stories of lion attacks and no one profits from holding whole herds of zebras at rapt attention with predictions about the best strategy to avoid impending lion attacks over the coming year. Humans, on the other hand . . .

Narratives of risk and fear are always more powerful than narratives of growth and stability. The stories suck us in. Financial news outlets know this. Remember: their job is to make a profit, not to make you a better investor. The best way to do that is to hook your ears and eyeballs with a steady stream of commentary about financial lions and what you need to do to avoid their claws and teeth.

Reduce stress with . . . more stress?

We attempt to avoid financial stress by educating ourselves. But is watching BNN or Jim Cramer education? Information consumption is not enough because, when it comes to personal finance, more information does not equate to better results. A higher-order skill must be honed: how to curate all that information. Sort the reliable from the unreliable, the relevant from the irrelevant, the effective from the ineffective.

Here’s a newsflash you should listen to: there is zero evidence that paying attention to analysts’ predictions will do you any good.

Smart ≠ Skilled

Otherwise intelligent people make bad investment decisions all the time. Intelligence can’t save you if you’re reactive rather than proactive. Stress short-circuits our big brains and switches on our short-term survival instincts. To make matters worse, all that information we are consuming can make us over-confident that our short-sightedness is justified.

It’s ironic that a truly long-term approach to investing is one of our greatest advantages as self-directed investors – one that professional investors can neither enjoy nor take away from us. And yet, so many of us undermine that advantage by voluntarily exposing ourselves to the financial news and, worse, buying into the idea that we should act on the information.

Don’t get me wrong, this is completely understandable. Keeping an eye out for threats is a fundamental part of our operating system because it’s necessary for survival. But we need to be able to discern between real lions and paper cut-outs of lions being pushed through the grass by those who have something to gain from our fear.

How to hack your stress response

Understanding this stress response is not enough because willpower can’t override our wiring. So, one of the best things an investor can do to improve long-term performance is to create an environment in which good decisions are easier and bad decisions are harder. I could make a long list of suggestions to accomplish this goal, but in the end, there is a simple solution to this vexing problem, and it’s one that you’re already familiar with: a financial plan.

Whether you do it on your own or with the help of a flat fee, advice-only mentor like me, building a plan means fitting all the pieces together – cash flow, tax planning, account management, investing, etc. When you do this, it’s only natural to step back, be more objective and take a long-term view. That is what allows you to see all the parts and how they will work together to achieve your goals. Like most things, it’s probably not as hard as you might think.

Your plan gives your financial life structure; it is the intentionally-designed environment in which the optimal financial decisions are made ahead of time. A financial plan defines what a healthy balance looks like for you – your state of homeostasis. It frees you from the need to react, improves your long-term outcomes, and gives you financial peace of mind. As Buffet says, you don’t need a high IQ; you just need a system to control the urges that get other people into trouble.

Running DividendStrategy.ca costs money. If you would like to support my efforts, you can donate here (half of all donations are given to Doctors Without Borders):

Superb Matt! Short-term thinking, short-term investing, and knee-jerk reactions can easily wipeout a life-time of sensible decisions. Each time on of these ‘crises’ arises (and they seem to be coming around more frequently), I shudder to think of some of our blog readers taking precipitate action that could cause very bad continuing consequences. In the vast majority of these situations doing nothing is by far the best course to take.

Absolutely, right on. Dave Stanley is not only the voice of reason, it’s plain horse sense. (Sorry zebras). Kudos Matt!

Thanks Eve!

I agree wholeheartedly, Dave. Our gut response to stress is to take action when the best thing is often to do nothing. If through this blog we can offer some validation for the “just stick with your plan” approach, that’s a great service, I think!

Well said. This is excellent advice for all DIY investors. Make a plan and stick to it. We’ve had one since 1995 and it has brought us a great stress free retirement.

That’s so great to hear. A financial plan is so vital, but in their valiant efforts to extract themselves from big bank financial advisors and their predatory fees, so many DIY investors are left without one and without the tools to create one. There is an enormous need for good, unbiased help on an as-needed basis.

Great article!

Glad you enjoyed it!

Simple smart advice Matt; all these decades of ‘crisis’ after crisis… and a return to norm seems to always happen. Sit on your hands and follow your plan. Easy to say, hard to do.

Exactly, Brent, there’s always a crisis but it is NOT easy to keep things in perspective without a plan.

Value investor Ralph Wanger had a different way of looking at zebras and lions.

From the 1989 book “The New Money Masters” by John Train.

“Zebras have the same problem as institutional portfolio managers like myself.

First, both have quite specific, often difficult-to-obtain goals. For portfolio managers, above-average performance; for zebras, fresh grass.

Second, both dislike risk. Portfolio managers can get fired; zebras can get eaten by lions.

Third, both move in herds. They look alike, think alike and stick close together. If you are a zebra and live in a herd, the key decision you have to make is where to stand in relation to the rest of the herd. When you think that conditions are safe, the outside of the herd is the best, for there the grass is fresh, while those in the middle see only grass that is half-eaten or trampled down. The aggressive zebras, on the outside of the herd, eat much better.

On the other hand – or hoof – there comes a time when lions approach. The outside zebras end up as lion lunch. The skinny zebras in the middle of the pack may eat less well but they are alive.

A portfolio manager for an institution such as a bank trust department, insurance company or mutual fund cannot afford to be an Outside Zebra. For him, the optimal strategy is simple: stay in the centre of the herd at all times. As long as he continues to buy the popular stocks, he cannot be faulted. On the other hand, he cannot afford to try for large gains on unfamiliar stocks, which would leave him open to criticism if the idea failed.

Needless to say, this Inside Zebra philosophy doesn’t appeal to us as long-term investors. We have all tried to be Outside Zebras most of the time, and there are plenty of claw marks on us.”

Oh man, that’s fantastic. Layers and layers of meaning and applications. Thanks!