I’ve heard that I should “own my age” in bonds but I’m worried that I’ll run out of money in retirement with such a conservative portfolio. Is there another way?

Susan’s Question:

I’m 64 years old and set to retire next year. I have saved $107,000 in my TFSA, $183,000 in my RRSP and will be receiving $27,500 per year from a defined-benefit pension plan. My husband, Steve, who is 67, retired two years ago and has an RRSP worth $251,000 and a TFSA worth $115,000. He doesn’t have a pension but received an inheritance a few years ago which has helped with our day-to-day expenses. There is $90,000 left in a non-registered account from that inheritance. We also have about $20,000 in our chequing and savings accounts. We own our home and don’t have any debts.

I think we have enough money between our savings and my pension for a comfortable retirement – maybe even a few big trips in the next few years, which is something we’ve been putting off for a while – but I’m not 100% sure. We’d like to be able to spend $85,000 per year – but I’m worried about the stock market. If there is a crash and we lose 40 or 50% of our savings, we could be in big trouble!

I’ve heard that retirees should “own their age” in bonds or have “100 minus their age” in stocks and the rest in bonds. So, either way, for us that would be about 35% in stocks and 65% in bonds. But I can see two big problems with this. First, I’m not sure that having only one-third of our money in the stock market will give us the returns we need so that we don’t run out of money. Second, to be honest, I’m just not that comfortable with bonds. Interest rates are better now than they were a year ago, but they’re far from risk-free and 65% of our portfolio seems like too much.

Is there a way to access the higher average returns of the stock market without having to worry about the next crash sabotaging our retirement?

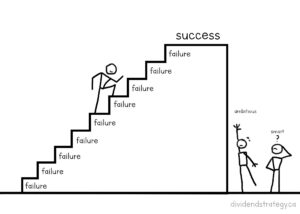

This is a great question and it stems from a very common situation. The stock market is volatile, and most investors want to minimize the volatility of their portfolio – particularly in retirement. But accepting lower returns in order to do so exposes us to longevity risk: the risk of running out of money.

In my opinion, rules of thumb like “Investors should own their age in bonds” or “Your portfolio should only contain 100 – your age in stocks” haven’t been useful for years. They were created in an era when bonds had a track record of generous interest payments, lower volatility than stocks, and low correlation with stock market returns. Even though interest rates are more normal than they have been for a few decades, bond prices have tumbled over the past year along with stocks, showing that they are not the safe haven many assumed they would be.

Bonds can and should still play a role in many people’s portfolios – in fact, because prices have dropped and interest rates have gone up, the future expected returns of bonds are better than they’ve been in a long time. Even so, investors have been looking for bond alternatives for years.

Are dividend-paying stocks a good alternative to bonds?

One alternative is blue-chip dividend-paying stocks. If you are in a position to build a well-diversified portfolio that provides you with the dividend income you need to live on, wonderful. But buying individual stocks is not for everyone, there are diversification issues whether you use individual stocks or an ETF approach, and there is a trade-off with appropriate international diversification because international ETFs (my preferred approach for gaining international exposure) don’t pay great dividends.

Fortunately, there is a simple way to enjoy the growth benefits of a portfolio weighted toward stocks and insulate yourself from stock market crashes so that your lifestyle is secure.

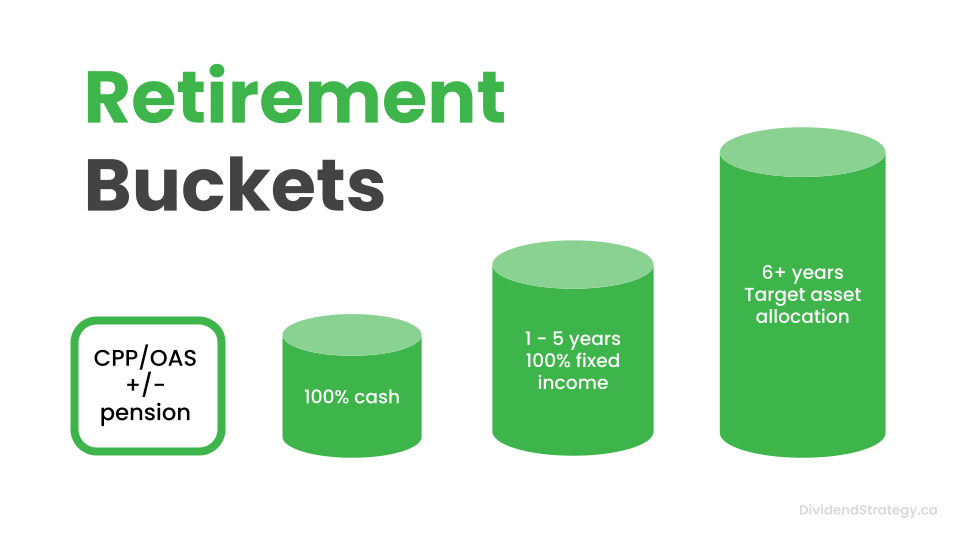

Retirement Buckets

When I work with my financial planning clients who are close to or in retirement, I love introducing them to the concept of “Retirement Buckets”. These are not separate accounts, but rather a useful way to think about retirement assets. Here’s how it works.

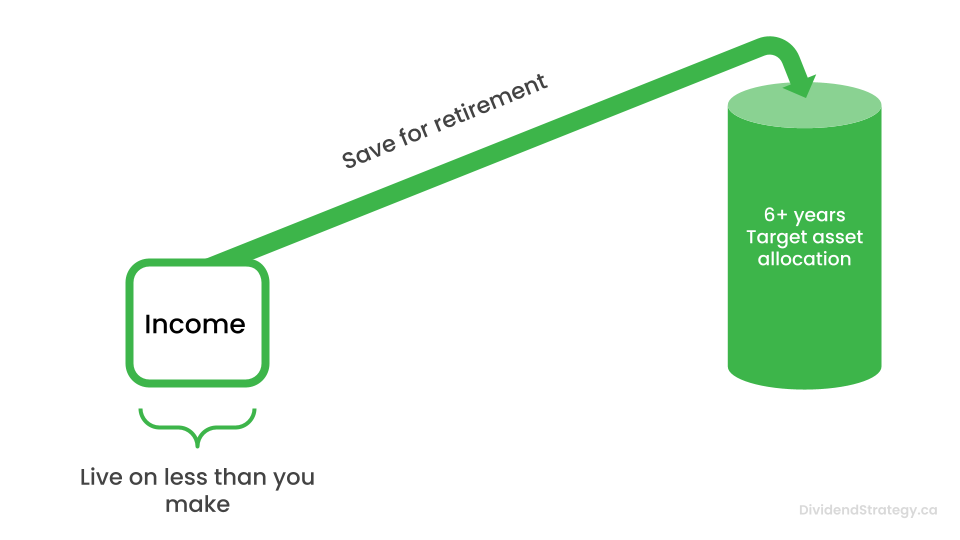

While working and earning an income, hopefully, you are spending less than you make and saving the difference. Those savings are invested for the long term based on your target asset allocation.

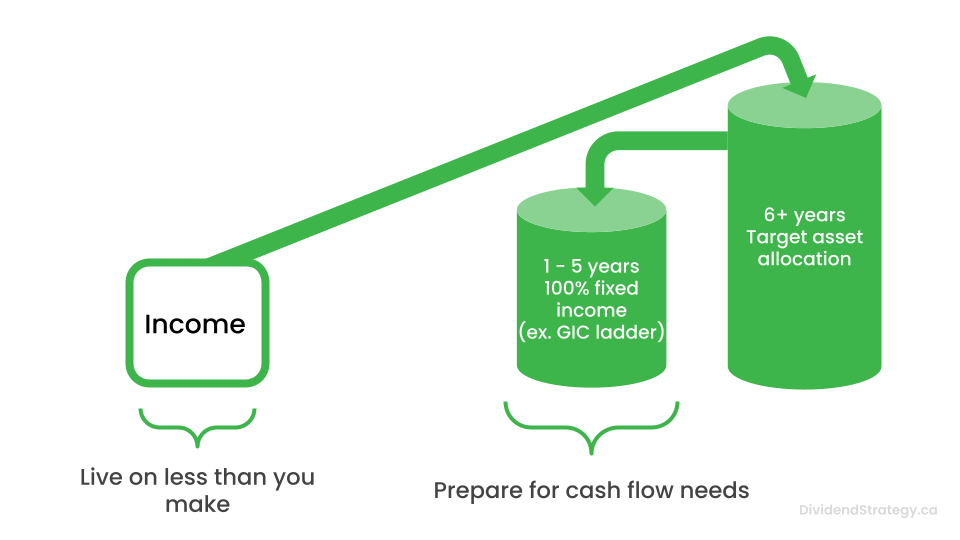

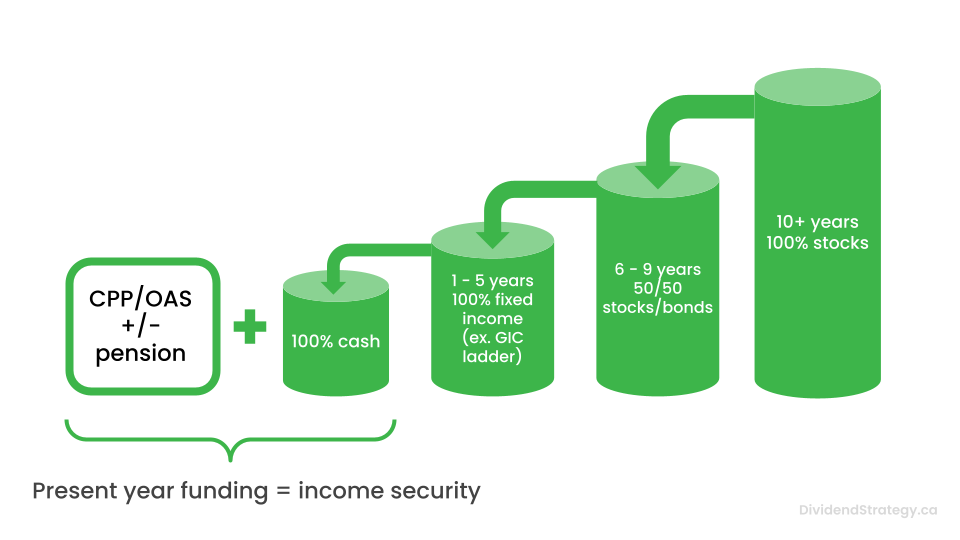

As you get within 5 years of retirement, you are going to need a new bucket. Why? Because history tells us that the stock market can be down in any five-year period. Any money that you are going to need within the next five years should not be in the stock market. Thus, we need to start filling a “5-year” bucket and investing that money in 100% safe investments. GICs are a good option here.

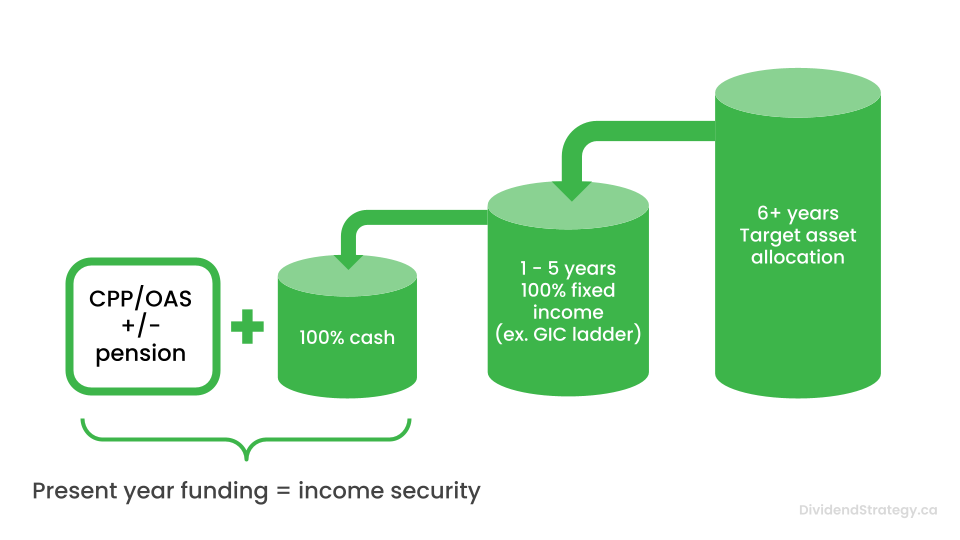

As you get closer and closer to retirement, that 5-year bucket fills up either with the investment returns from your first bucket or with new contributions. This second bucket is now a permanent part of your financial plan. When you are within a year of retirement, your 5-year bucket is used to fill one last bucket: your annual income bucket. This is the liquid cash you will need in combination with other sources of retirement income to fund your lifestyle for the coming year.

Retirement income that is insulated from stock market volatility

I’ve seen numerous variations on this idea, but this is the basic structure. It essentially guarantees that the next five years of income will be there when you need it. If you use GICs in that 5-year bucket, the interest also provides you with some inflation protection. At the same time, the bulk of your portfolio can be invested using an asset allocation that gives you access to the long-term wealth generation of stocks. This provides security against longevity risk while short and medium-term volatility risks are addressed with guaranteed 5-year cash flows.

The Retirement Bucket model is also flexible. If five years of income security is not good enough for you situation, make it seven years. I’ve also seen some models in which there is another bucket added between the long-term bucket and the 5-year bucket such that very long-term investments might be 100% equities, those that will be needed in 5 – 10 years might be 50/50 equities and bonds, etc.

How your retirement buckets are set up should be customized for your situation. It’s one of my favourite parts of mentoring because it’s so simple, yet so effective.

Susan and Steve’s Retirement

Let’s see how retirement buckets can help Susan and Steve. For this example, we’ll use Financial Planning Canada estimates that equities are likely to provide a nominal rate of return of 6.87%, while fixed-income investments return 2.70%. Furthermore, we’ll assume that inflation will average 2.5% over the course of Susan and Steve’s retirement.

Even though there is great evidence to support delaying CPP, for now let’s also assume that Susan and Steve do what most people do and start their CPP at 65. We will also assume they receive what the average Canadian does – about 55% of the maximum.

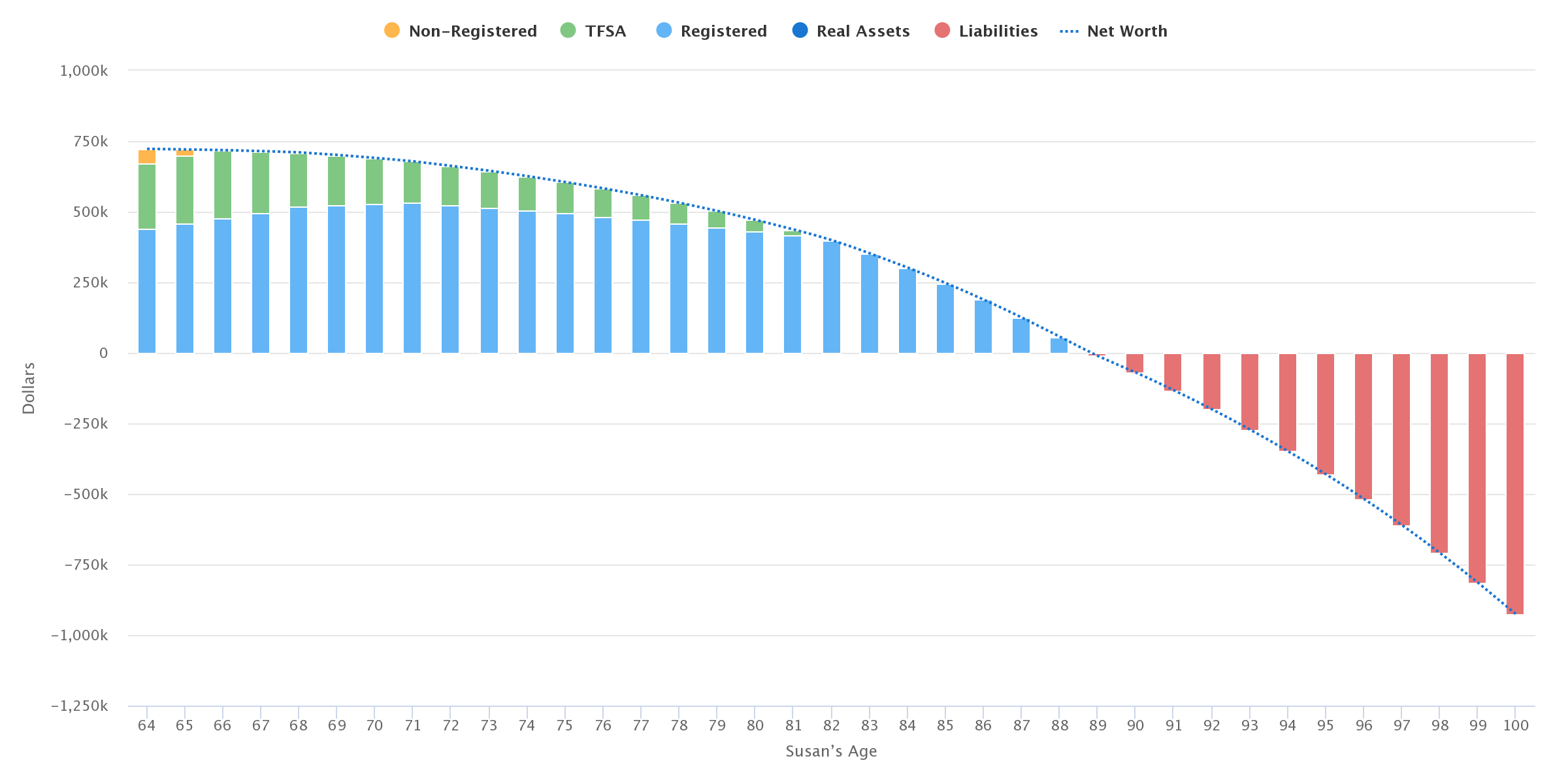

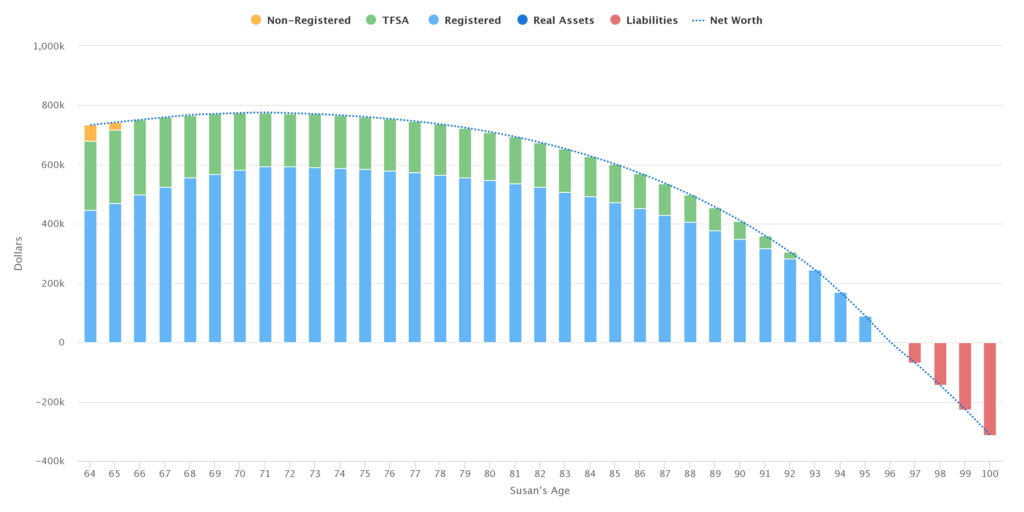

When I am creating projections with my clients I prefer to run scenarios all the way out to age 100 unless there is a reason to predict a much shorter life expectancy – best to err on the side of caution. If Susan and Steve were to use an asset allocation of 35% stocks and 65% bonds in their retirement accounts, here is what their financial future might look like:

Fig. 5: Susan and Steve’s Net Worth over time:

Unfortunately, using a 35/65 portfolio, Susan and Steve risk running out of money in their late 80’s – possibly sooner if they suffer an unexpected financial shock like long-term care costs or the premature death of one spouse (which would mean the loss of one spouse’s OAS, some CPP, and all income-splitting benefits).

Even though a 35/65 portfolio might feel safe in the short-term because it would protect Susan and Steve from stock market shocks, they have essentially traded that risk for another one: running out of money.

Let’s see what happens if Susan and Steve adopt the Retirement Bucket approach.

Susan and Steve’s Retirement Buckets

An axiom of financial planning is: don’t take risks that you don’t need to take. Thus, we are trying to figure out the most conservative asset allocation that will allow Susan and Steve to enjoy their retirement and have confidence that they won’t run out of money. This is where financial planning software really shines.

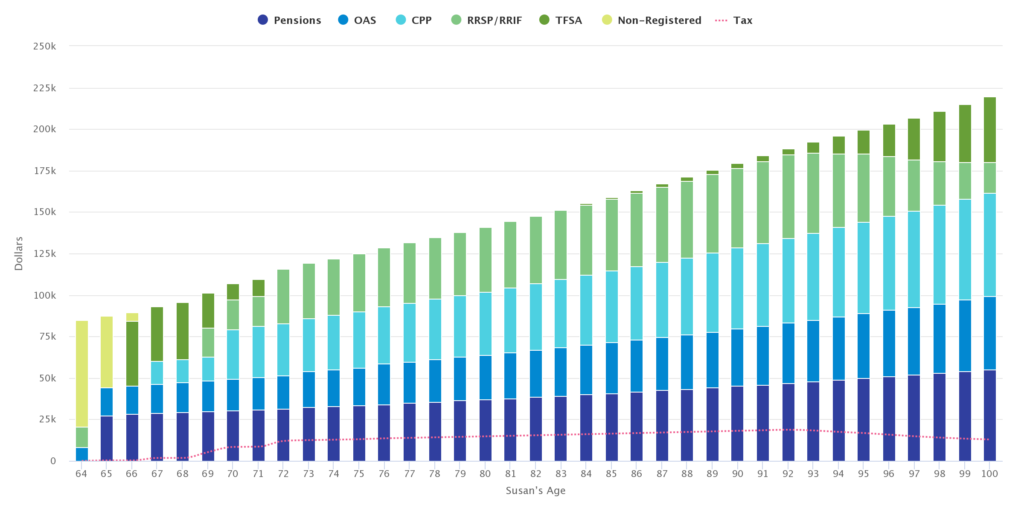

The first step for Susan and Steve is to figure out how much money they will need to draw from their investments each year. Let’s not forget, Susan is fortunate that she has a defined-benefit pension of $27,500/year (and it includes a “cost of living adjustment” (COLA)). In addition, they will receive about $15,000/year from CPP and $17,000/year from OAS (both fully indexed to inflation) combined.

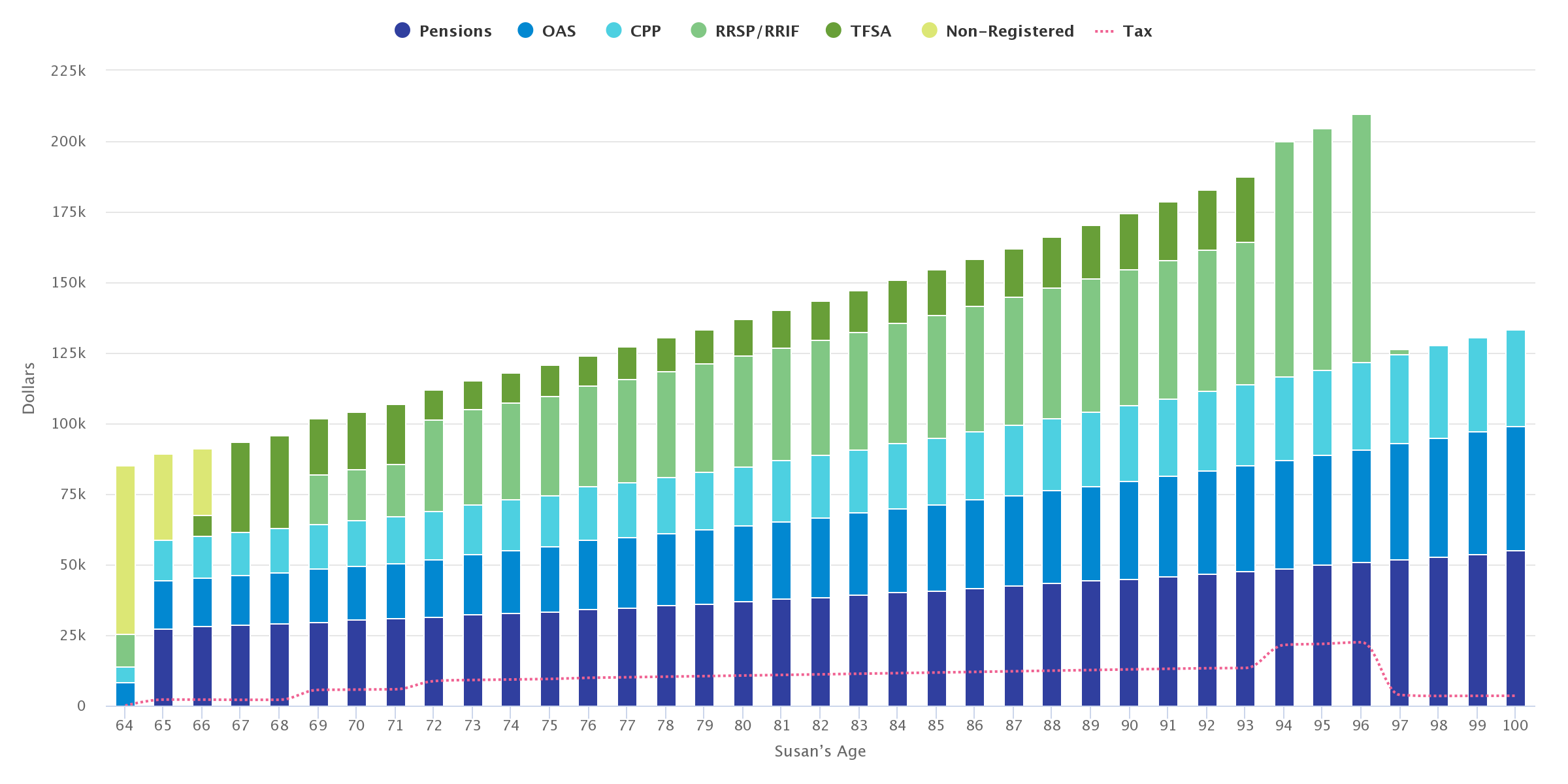

To fund their $85,000/year (in today’s dollars) living expenses, Susan and Steve will need to draw on their investment accounts. For this simple scenario, we will have the couple draw from non-registered accounts first, then TFSAs, then RRSPs. Here is where their income will come from in retirement, year by year.

Fig. 6: Susan and Steve’s Sources of Income in Retirement

As you can see, after their non-registered funds are used up, Susan and Steve’s income will come from a mix of Susan’s pension, CPP, OAS, RRSP/RRIF, and TFSA withdrawals.

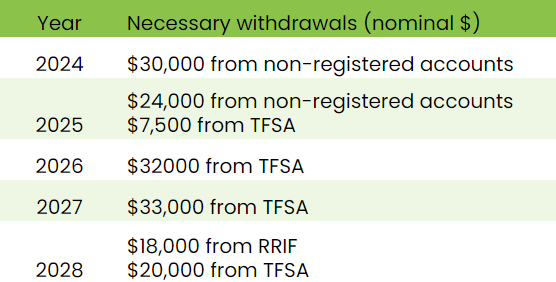

Above and beyond pension, CPP, and OAS income, Susan and Steve will need the following amounts from their accounts over the next five years:

Fig. 7: Susan and Steve’s cash needs from their retirement accounts

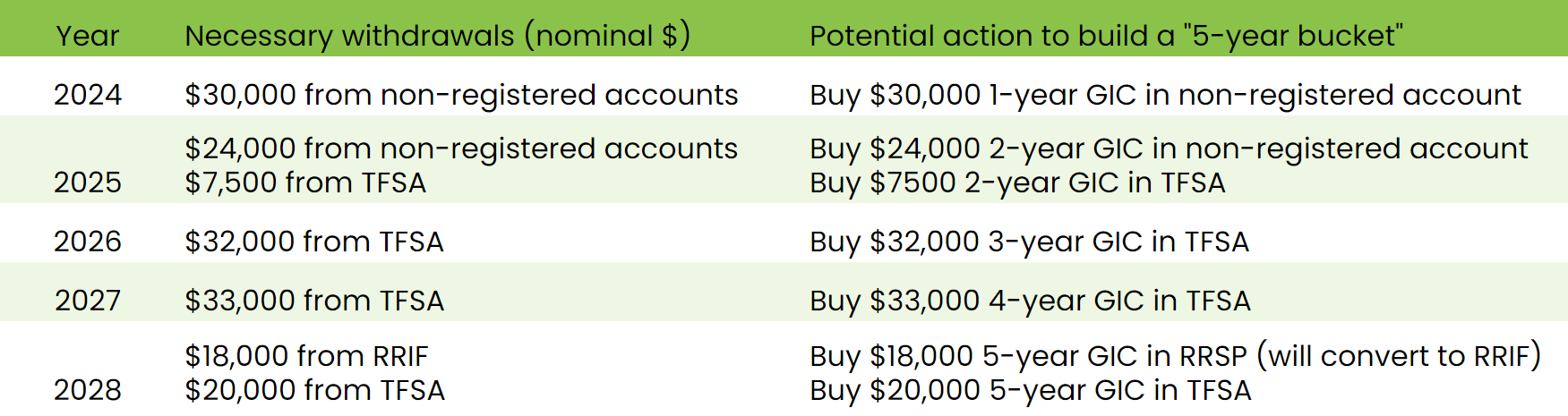

To fill their 5-year bucket and safeguard their living expenses for that time, all Susan and Steve would have to do is buy GICs in the appropriate accounts equal to those amounts, like this:

Fig. 8: Susan and Steve may opt to build a GIC ladder in their 5-year bucket

How can the rest of Susan and Steve’s savings be invested?

Given that their spending needs for the next five years are fully protected, Susan and Steve’s asset allocation question can be seen in a new light because they no longer need to worry about short-term market volatility.

How much additional fixed income do they need? If we add up the amounts in Figure 7, we get $154,500, which is 20% of Susan and Steve’s liquid assets that will be allocated to fixed-income in their 5-year bucket.

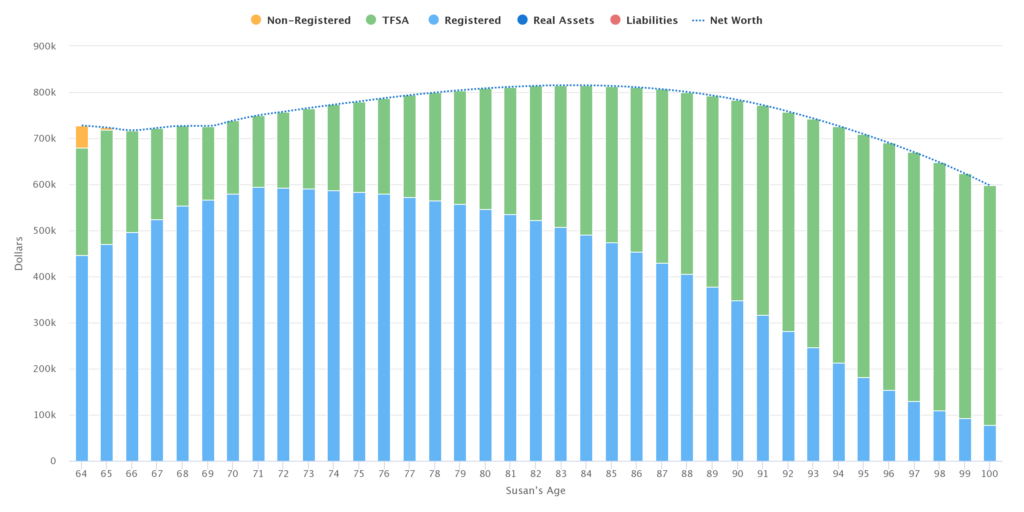

If they were to invest the rest of their money, about $580,000, in stocks, they would have an overall asset allocation in their retirement accounts of 80% stocks and 20% fixed income. But I’ve run the numbers and that’s more aggressive than they need to be. Susan and Steve will be just fine with a 70/30 split, as you can see here:

Fig. 9: Susan and Steve’s Net Worth Over Time Using Retirement Buckets

This is a sustainable scenario because Susan and Steve wouldn’t run out of money until their late 90’s and even then they haven’t touched the equity in their home which would provide ample liquidity.

But there is another strategy that will make Susan and Steve’s retirement even stronger. Simply delaying CPP until age 70 significantly improves the picture:

Fig. 10: If Susan and Steve delay their CPP until age 70, their situation improves dramatically

Related: Comparing CPP at 60 vs. 65 vs. 70 . . . The results might surprise you

Susan and Steve’s sources of income in retirement

Things are looking good for Susan and Steve, but the really wonderful part about their financial plan is revealed when we look at their sources of income. Although they have significant assets invested in the stock market for growth, their income is insulated from stock market volatility because it is coming from Susan’s pension, CPP, OAS – all of which are indexed to inflation – and the 5-years’ worth of GIC’s that they have set aside from their stock holdings.

Fig. 11: Susan and Steve have diversified sources of income that are protected from stock market volatility and largely adjusted for inflation

One last point about asset allocation

Some of you might be thinking that a 70/30 portfolio is still too aggressive for a couple on the cusp of retirement – and in some cases it certainly is. But in Susan and Steve’s case, that’s not the whole story because we haven’t taken into account Susan’s defined-benefit pension. Because it is guaranteed income, such pensions can be considered part of the couple’s fixed income. We can estimate the value of Susan’s pension at approximately 25 times the annual benefit which, in this case would be $687,500.

If we add this to the 30% fixed income component of their liquid assets (~$220,000), we get a more accurate picture of Susan and Steve’s total asset allocation: 64% fixed income and 36% equities. Coincidentally, we end up right in line with those out-of-date rules of thumb, but this time with a solid financial plan that will allow Susan and Steve to enjoy their retirement without worrying about running out of money.

Is your retirement plan on track? Would you benefit from an analysis similar to Susan and Steve? I can help.

Advice-only financial Planning

No products, just personal, unbiased advice. Confirm you're on the right track. Understand how much you can safely spend in retirement and when it's okay to spend more. Calculate CPP, OAS and know if delaying those benefits is right for you.

Basic financial plans starting at just $900+tax. Includes a 1.5-hour strategy session with Matt, 4 - 5 financial projections, a summary of the findings, and a full report for the plan of your choice.

Book your sessionLearn more

I notice that you suggest generating income from the non-registered account first before drawing down the RSP account. What is the reasoning behind that?

Great observation and question. The reasoning is that keeping as much money as possible in registered accounts growing tax-free for as long as possible will lead to greater wealth. There is some nuance to consider such as pulling some money out of RRSPs in very low-income tax years, but this is the general principle. Non-registered investments are simply less tax-efficient.

Hi Matt,

First, thank you very much for your blog, I find it very useful and informative.

Your idea of filling buckets ahead of time to save us from the markets gyration is very clever. It helps us from having to dip into our RRSP funds on bad years, giving time to the markets to recuperate some of the losses. But retirement will last more than 5 years. When do we transfer funds from the RRSP to the 5year bucket after we skipped a year due to a downturn? Do we double dip the following year? What if the downturn lasts 2 years like it did in early 2000?

Thank you for taking the time to rely.

Hi Fred,

The way I like to see this approach used is that every year a new 5-year GIC will be purchased unless circumstances are very dire in the markets, in which case the purchase can be delayed. But, you’re right, at some point, you will need to “catch-up”. Those decisions depend on many factors, so it’s difficult to give general advice. Should you not buy a GIC at all? Buy a smaller amount? Should you sell only from the bond portion of your portfolio to buy the next GIC? The good news is that there is a lot of flexibility with this approach, but no one ever said cash flow planning was easy and it can be very useful to get a second opinion when things are uncertain.

I have seen many variations of the bucket approach, Daryl Diamonds version comes to mind, all are generally sound advice. I am not sure I agree with your suggestion of using TFSA before RRSP/ RRIF withdrawal. Many bloggers do quite well in the 65 to 70 age group for analysis, but seem to gloss over the fact that RRIF withdraws are mandatory and increase annually.after age 71. My plan will be to use TFSA’S last, and I added a twist, to withdraw max annual TFSA contribution “In Kind” from my RRIF and transfer in securities to said TFSA. I am happy to take the immediate tax hit, to enjoy the future growing tax free dividend returns. Truth be told I am still working (69) and plan to till 70-71. As I have no company pension plan, I have delayed both CPP & OAS to max date possible ( 70 ), and plan to work part time but only enough so as to not trigger OAS repayment. Being debt free by the time you retire is also a huge planning advantage for those still working and not yet there retirement wise.

Good eye re: drawing from TFSA before RRSP or vice versa. The default setting for the software I use is to draw from non-registered funds first, then TFSA, then RRSP but this is not always optimal, as you rightly point out. In fact, I ran Susan and Steve’s scenario again with them drawing from RRSPs rather than TFSAs from age 65 to 71 and their final after-tax estate value was slightly improved. It wasn’t the focus of this post, but perhaps an interesting topic to explore in the future. Thanks for the comment, Andrew.

Hi Matt, thanks for posting this interesting take on the retirement bucket approach.

I was wondering what the effect, if any, would be on when to take CPP if life expectancy was assumed to be 90 rather than 100.

Drawing down retirement funds seems to be an ongoing fine tuning exercise. There are great comments here and it’s interesting to hear what others are thinking/doing. I do agree with Andrew’s comment regarding feeding the TFSA yearly by transfers in-kind from the RIF fund.

Hi Mark – Even if life expectancy is average (early to mid 80’s), it is best to delay CPP to age 70 if you don’t need the funds. The longer you live, the more beneficial this delay will be for you.

Hi Matt – just stumbled upon this post. Great approach to sequence of returns risk. Would it be most tax efficient to draw down from an RRSP up to the maximum basic personal amount (BPA) early on and then top it up using taxable accounts? Otherwise a person may be in a larger bracket when the RRSP converts to a RRIF? Thoughts?

Great question, Mike. Yes, it’s often a good idea to withdraw from your RRSP in years when your income would otherwise be very low. If you have no other income, withdrawing up to the BPA is pretty much always going to be worthwhile. Above this you need to weigh the relative cost/benefit of lower tax vs more assets growing in a tax-deferred manner. The analysis gets complicated by assumed rates of return, other sources of income (including CPP and OAS), time horizons, etc. Financial planning software shines for this kind of thing.

Very interesting article, thank you!

I have a question about rental income? My children rent two condos from me and I expect them to so for a while due to the high cost of living in Vancouver. How do you treat rental income for the purposes of bucketing? i.e. is it similar to a pension plan, cash, bonds, stocks etc.

Good question. I would consider it like fixed-income while retaining sufficient liquidity for repairs, vacancy, etc.